Dan Kirchoff

Mythical Creatures of Maineby Christopher Packard

In 2020, during the COVID pandemic, I found myself busy with a 43-illustration project. I was illustrating Christopher Packard’s new book, “Mythical Creatures of Maine,” which was about critters in Maine’s woods and waters that don’t actually exist (at least to our knowledge). These are stories from the French-Canadian communities, the logging camps and the Wabinaki Native American Confederacy. I had 11 months to create the illustrations and had a blast doing it, all in pen-and-ink with color added in Adobe Photoshop. Additionally, I created maps showing where these supposed critters are found, including Maine, New England and the Canadian Maritimes.

The “celofay” was an invention of the French Canadian community, famous for throwing its voice and confusing anyone in the woods trying to see it.

The “billdad” is one of my favorites. Invented by the logging camps, it lives on a single remote late in northwestern Maine. Reported to be a beaver with legs like a kangaroo and a beak like a hawk, it would leap out over a lake and smack a fish with its tail, then drag the fish to shore to eat.

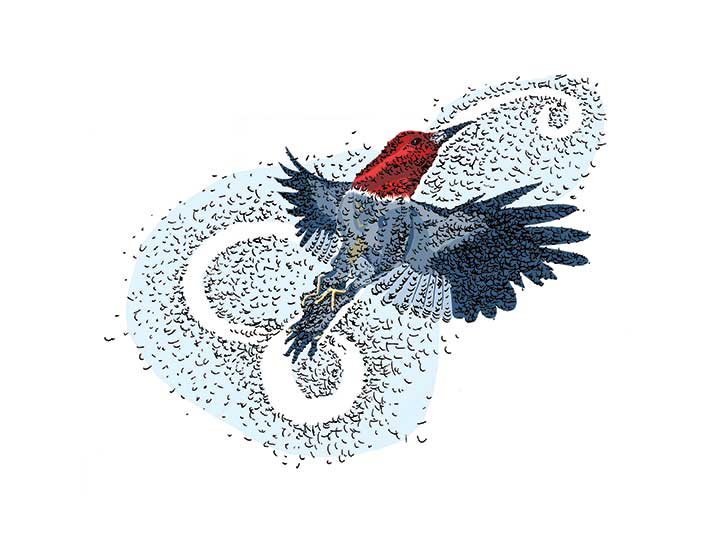

The “kaput-bird” was odd indeed. One wing was shorter than the other, so it only flew in circles. Once it got frightened, it would fly is smaller and smaller circles until it flew up its own derriere, so to speak. At that point, it would fall to the ground and try to straighten itself out.

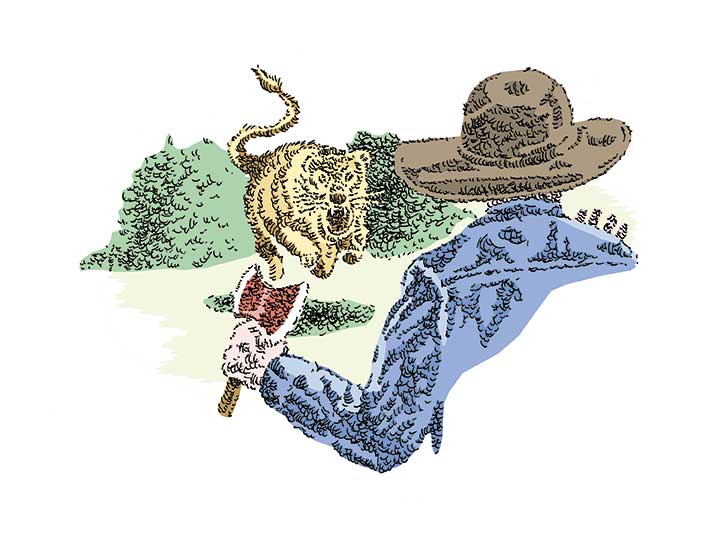

The “come-at-a-body” only appears at night, when you’re in the woods alone, and you smell like rum. Invented by the logging camps, it would run at you, scaring you half to death, and then stop just short of attacking, wandering off as if nothing had happened.

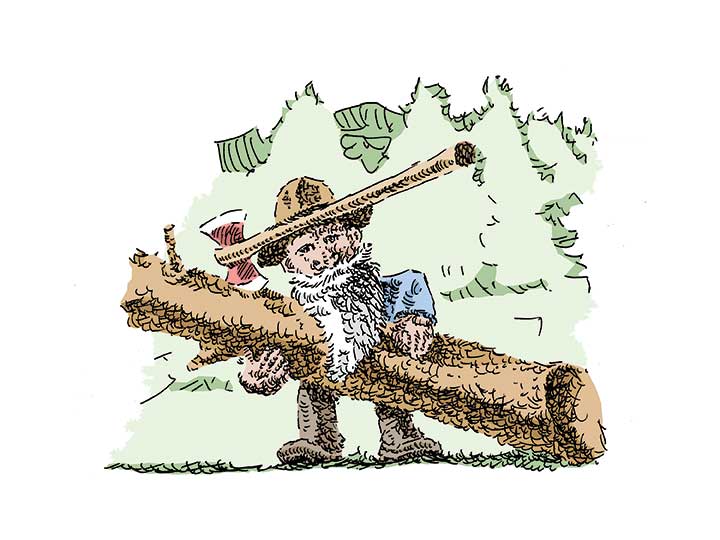

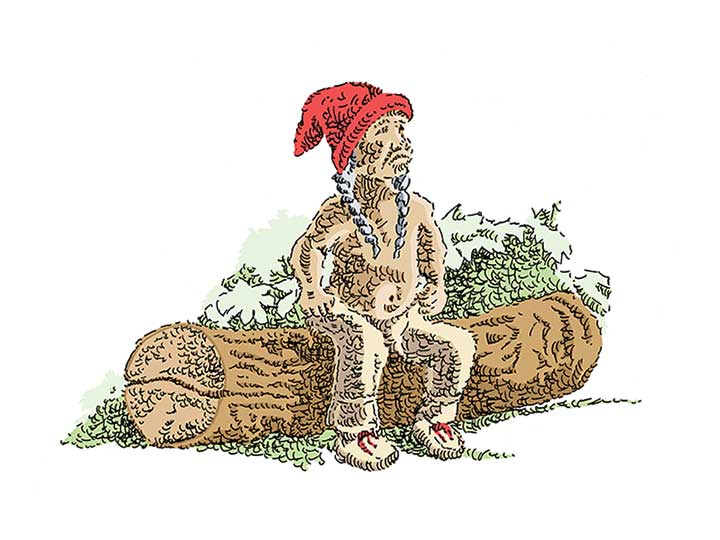

“Sock Saunders” was the guy loggers would blame if things went wrong at camp. An axe goes missing? Blame Sock Saunders. Tree falls in the wrong direction? Sock Saunders. Loggers would also shout “You didn’t get me that time Sock Saunders” even if things went right.

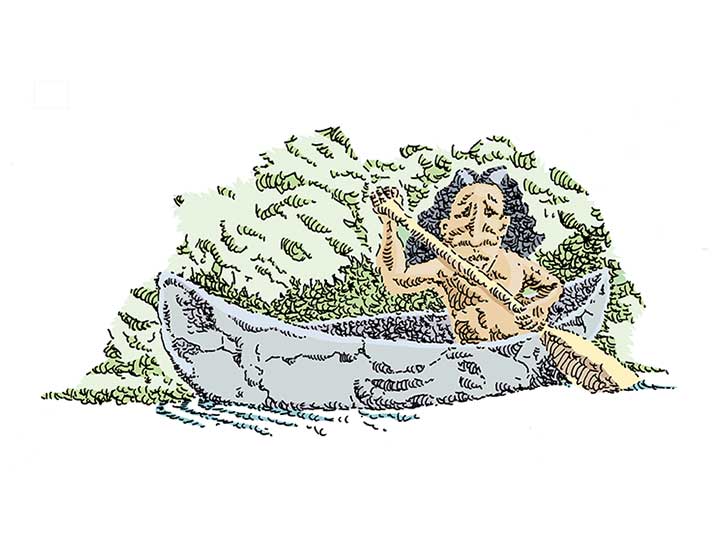

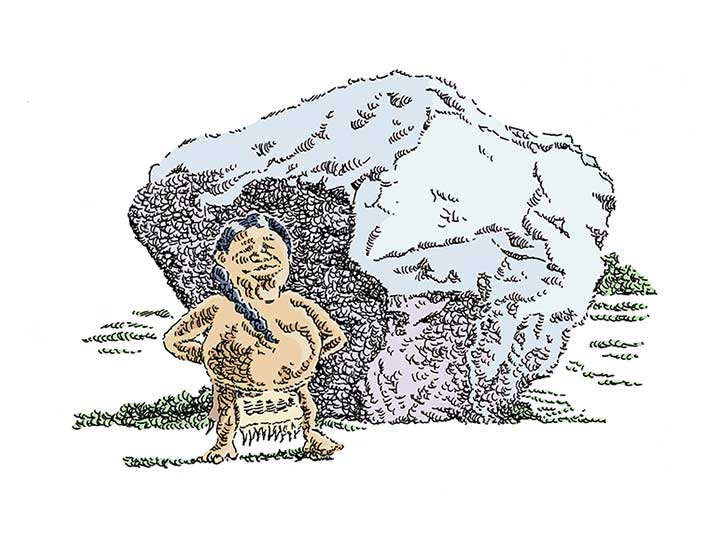

River elves or manogamasak are Wabanaki little people, helpful but shy and self-conscious of their ugly appearance. It would be extremely unwise to laugh at them or stare.

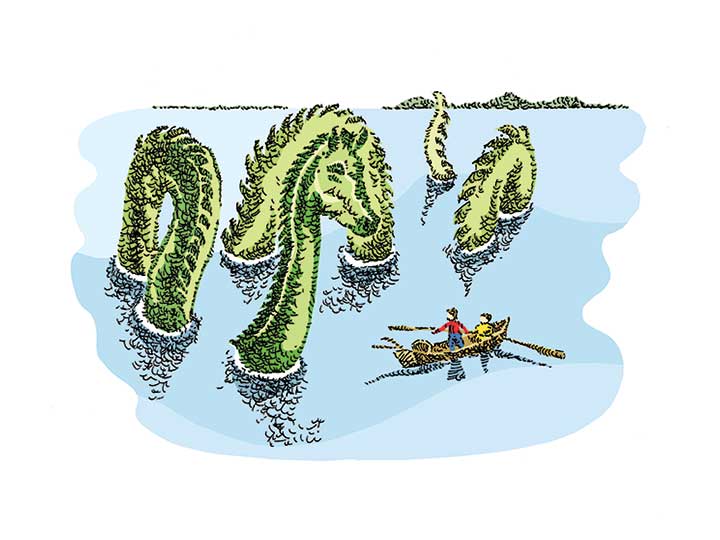

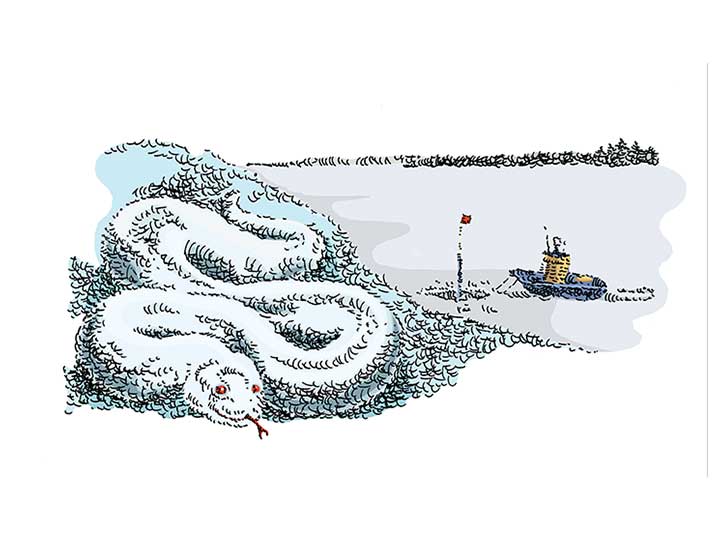

Hundreds of sea serpent sightings have been recorded in the Gulf of Maine. These giant serpents are impressive but seem to be largely harmless.

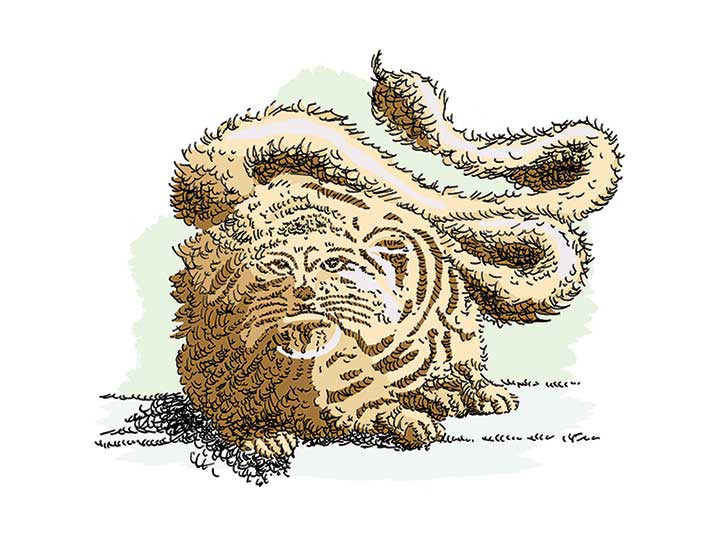

Sidehill gougers have uneven left and right legs so they can walk around a hill and keep their back level. They are responsible for “gouging” out deep paths on hillsides.

Silent elves or kiwolatomuhsisok are native little people who look like chldren or little old men, sometimes with long white beards. They don't mind being seen and they never say a word.

The will-am-along is very secretive and only glimpsed out of the corner of the eye. It has the habit of dropping poisonous lichen balls into the eyelids and ears of sleeping people.

A will o’ the wisp appears as ghostly dancing lights seen floating through the forest at night near water and wet ground. They’re suspected of leading travelers astray, never to be seen again.

If you are hiking on a rocky slope and see a recently broken rock or a new rockslide, it's likely the work of a wedge-ledge chomper. They can be as large as a car or small as a football, but rarely seen due to their perfect camouflage.

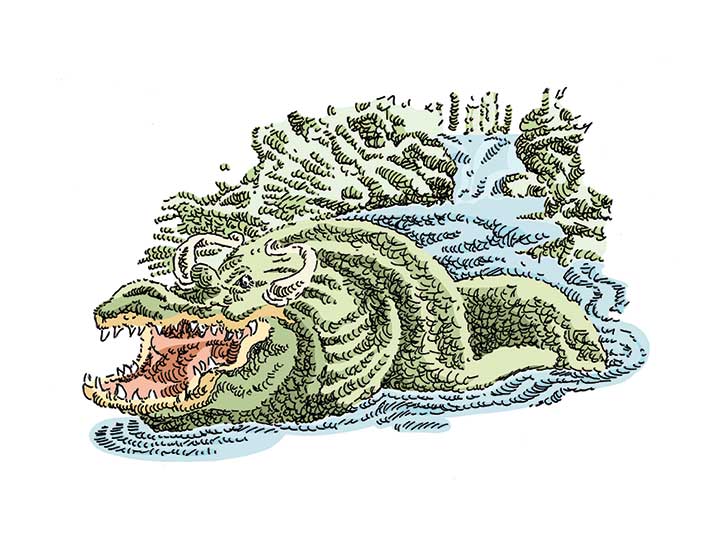

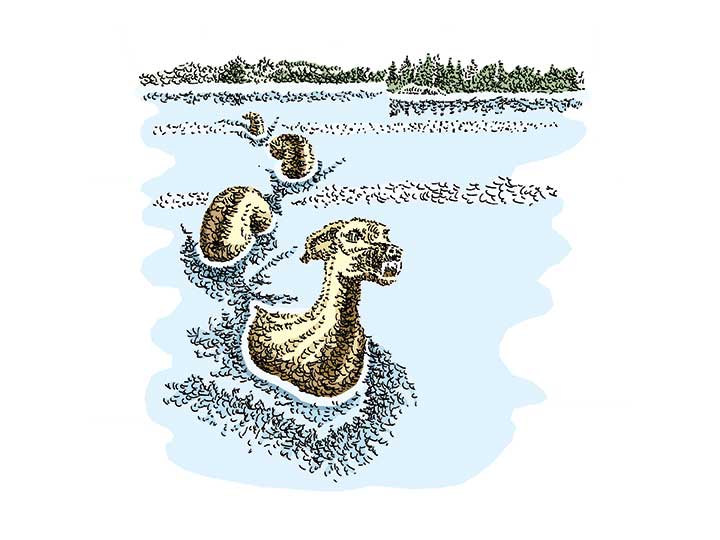

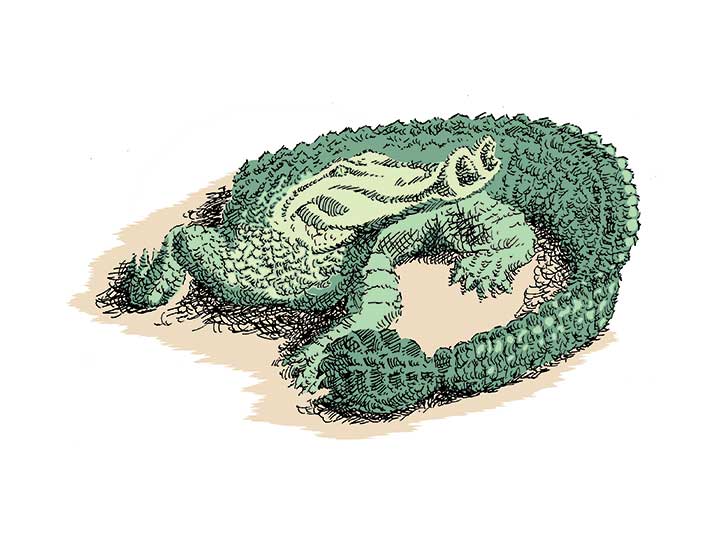

The weewillmekq is a Wabanaki great horned water serpent. It is said to be the rulers of the world below the surface with fiery eyes and sharp teeth. It has poisonous slime but also cunning and magic.

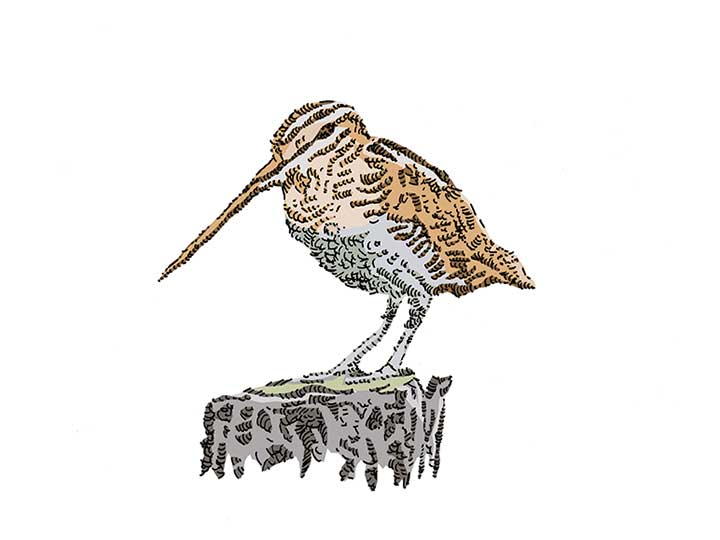

The snipe is a chubby-bodied, mid-size brown bird of freshwater wetlands. They actually exist despite the pranks played over the ages of “snipe hunting” in the woods on newbie campers.

Snow snakes can be quite deadly in the winter due to their perfect camouflage and chilling venom. Beware their yellowish burrows in the snow.

Trees don’t squeak. That’s the tree squeak you hear. These little creatures make a racket when the wind blows because they are helpless if they’re blown off their branch.

When hiking, always stay to the left of any puddles or boggy areas you encounter, or the one-armed wamfahoofus may grab your boot. It was discovered by Dr. Francis Boott in the White Mountains in the 1800s.

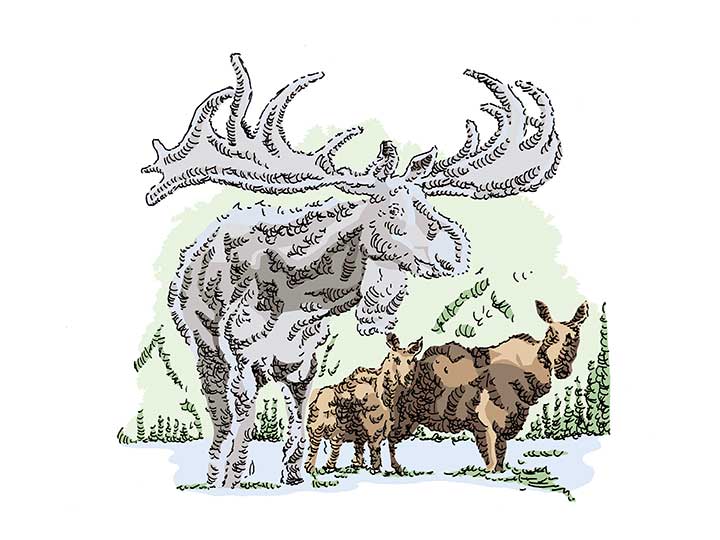

Specter moose are giant white moose that can aggressively command respect or simply disappear in an instant. Some say that it is the spirit of all moose.

Stone dwarves are Wabanaki little people that live in caves, rocks and mountains. The bigger the home, the more of them that live there. in interactions with them, respect and politeness are key.

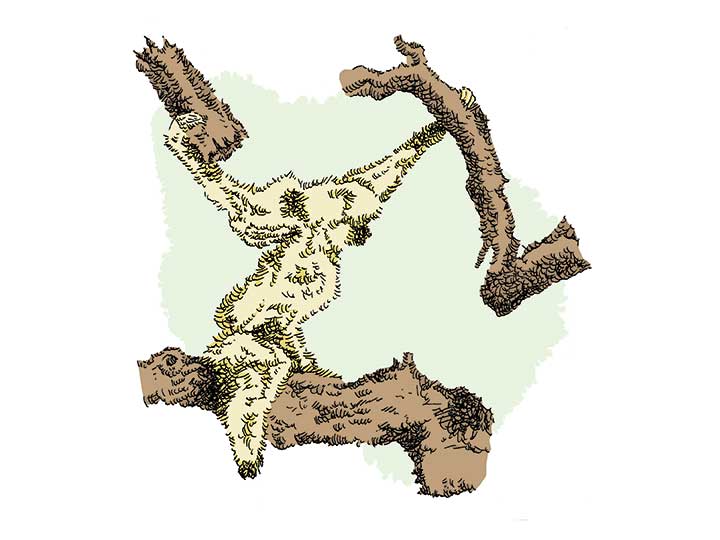

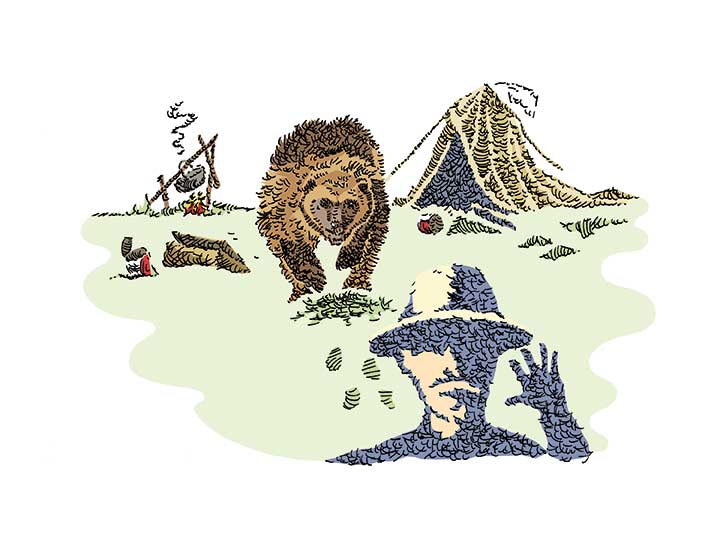

The agropelters are mean little ape-like creatures with the dangerous habit of throwing dead branches at people who disturb them. Their favorite target seems to be lumberjacks’ heads....

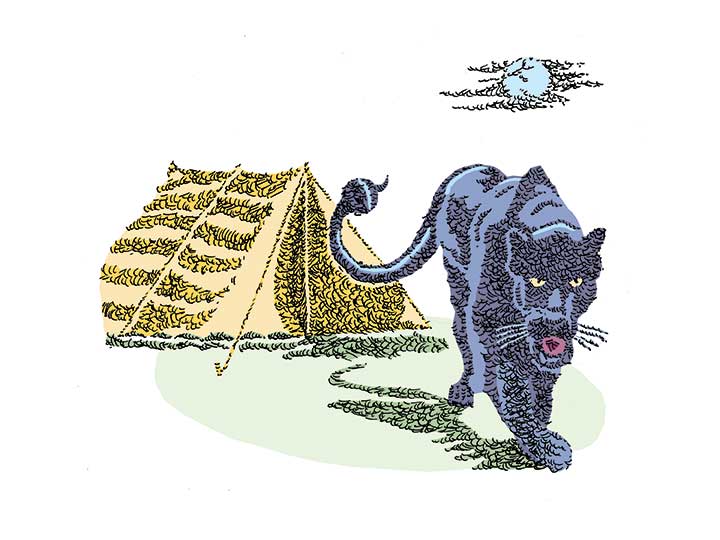

Unsuspecting lumbermen were often lured out into night by the human-like calls of the ding-ball. Their reward was to be cracked in the head by the cat’s tail.

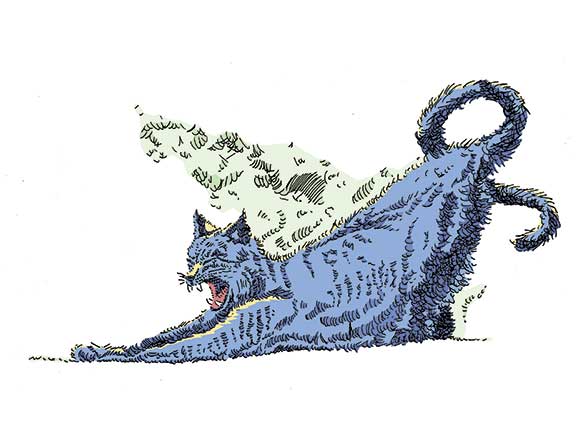

The dingmaul is a majestic and gentle mountain cat, content to lie about on rocks unless you make it happy or scared. Then watch out for its wildly swinging tail.

There have been hundreds of sightings of lake and river serpents throughout the region since prehistoric times.

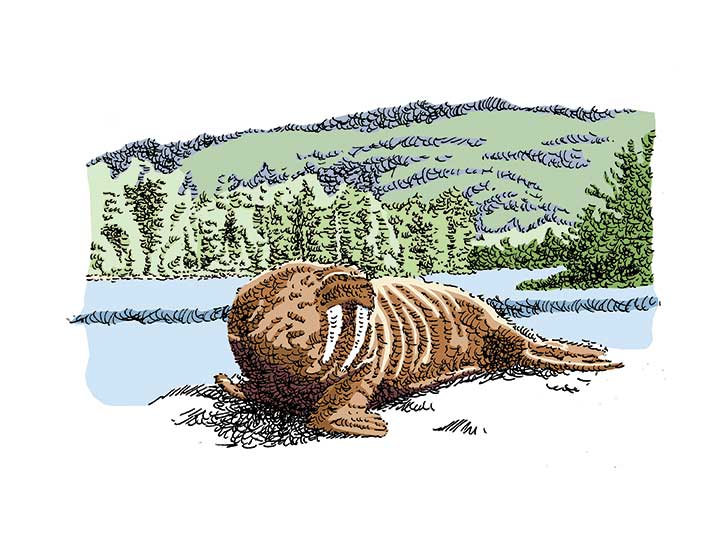

Deprived of their marine surroundings, these landlocked walruses are more dangerous than their marine cousins.

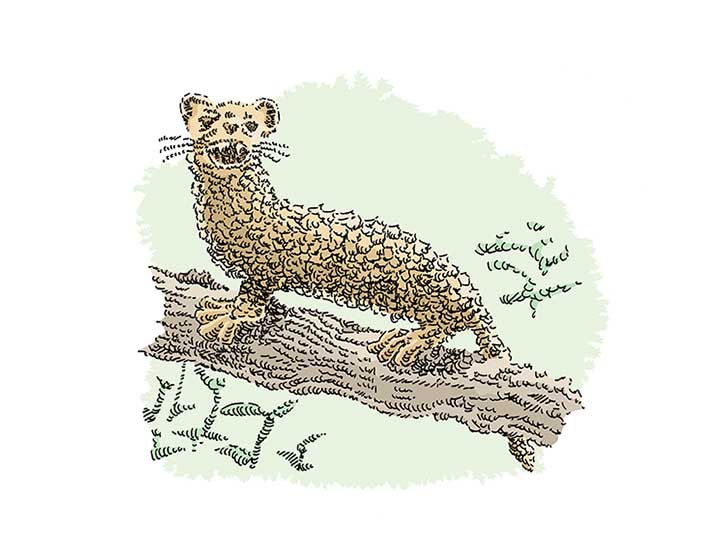

Also known as the “Indian Devil,” the wolverine was the only animal Wabanaki hunters feared. With the wolverine long extinct in Maine, the name lunksoos was frequently applied to other creatures.

Sometimes taking human form, lumpeguin can occasionally be seen frolicking in the waves near the sore. Don’t let their size fool you — their powerful magic makes them worthy of respect.

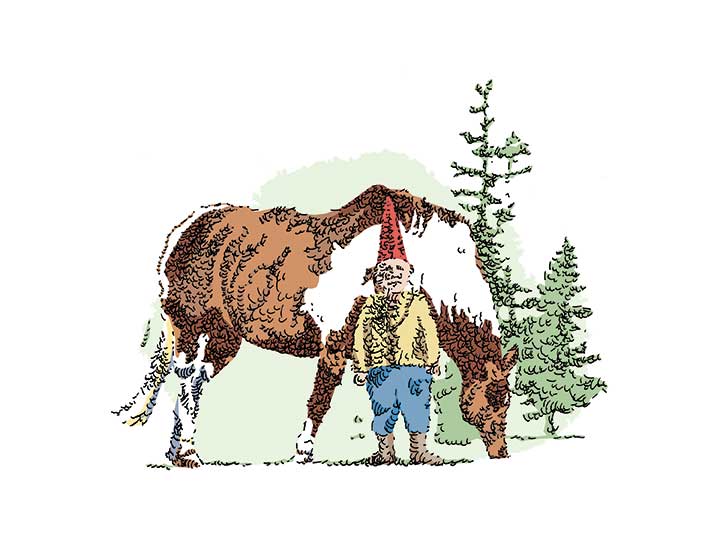

Lutins immigrated here with the French. These little elves like to attach themselves to a home, where the can be helpful or mischievous.

Despite being designated as extinct in Maine, hundreds of mountain lion sighntings are reported each year throughout the region.

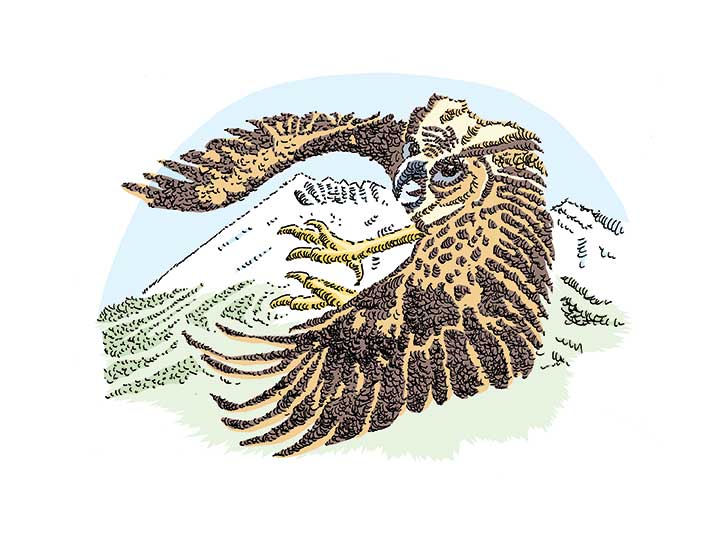

Pamola is a giant winged being who lives atop Katahdin. For centuries he kept people off the mountain. This powerful creature should be treated with respect.

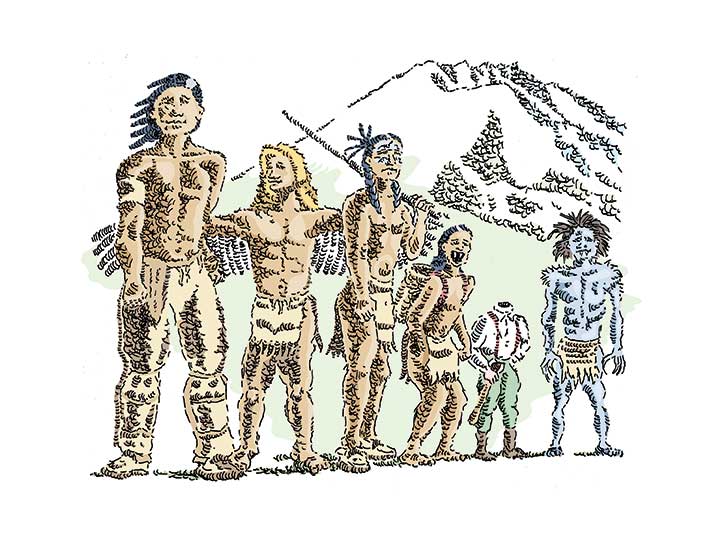

Six types of giants can be found across the Wabanaki territory. From left, magician giants Guskap, thunder giants, stone giants, man-eating kukwesuk, headless giants and the cannibal wendigo.

What it lacks in mouth, the dugavenhooter makes up for in nostrils. It pounds its unsuspecting pray with its tail into a gaseous pulp, which it can snort up through its nose.